When we think of blockbuster movies we often think widescreen! Thick black bars at the top and bottom of the screen instantly clue viewers into the fact they’re watching a film fit for the silver screen, not a cheap TV show. For aspiring filmmakers, those black bars are a cinematic cheat code. YouTube filmmaking and Unreal Engine tutorials insist on adding black bars to make live-action footage and digital renders look like a proper film rather than internet video or game footage. In fact, video games often add black bars when transitioning out of gameplay and into a cut scene. Widescreen has long been a sign of legitimate cinema as opposed to the boxier rectangles of straight-to-DVD or TV movies.

But this may be about to change, or it may have already changed. We’re seeing more and more instances of blockbuster movies throwing off the black bars for “taller” aspect ratios. This gradual shift away from widescreen may just seem like a nerdy detail for film enthusiasts, but in actuality, this change is a fascinating nexus point of the relationship between artists and audiences, between cinema and streaming and between the past and the future.

Let me explain…

A Brief History of Widescreen

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before - A new home entertainment technology has hit the scene, sending Hollywood studios into a panic as they scramble to figure out how to entice audiences back to cinemas when they can just as easily stay home. These days it’s streaming, but back in the 50s and 60s, it was television itself. Thankfully Hollywood had a hardware solution to the threat posed by television.

Up until then, most movies were presented in the Academy Ratio also known as 1.37:1 or 4:3. It was an almost perfect square and that square fit snugly on the television sets being rolled out across Europe and the States.

So to beat the lure of that small square box, Hollywood rolled out Widescreen also known as Cinemascope or just Scope. In truth, French filmmaker Abel Gance had invented widescreen decades earlier for a sequence in his epic, Napoleon, but the craze didn’t kick off until the middle of the century.

Napoleon (1927) with its ultra-wide 4.00:1 aspect ratio.

Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) with the more familiar 2.39:1 aspect ratio (most widescreen movies use this ratio).

The common element with a lot of widescreen releases was their epicness. The first Cinemascope release was the biblical epic, The Robe (1953) and David Lean’s great epics like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965) filled their wide images beautifully.

And this emotional logic has stayed with filmmakers and audiences ever since. If you want something “cinematic,” you go widescreen!

Or do you?

The Push Back On Scope

The rapid rollout of Scope in the 50s and 60s was a marketing gimmick rather than a creative choice and many acclaimed directors hated using it. Howard Hawks, Fritz Lang and Vincente Minnelli all disliked it.

Great filmmakers know that widescreen is not a technical standard, it is merely another storytelling tool. Steven Spielberg always considered what kind of action would take place in his films before deciding on an aspect ratio.

Indiana Jones was perfect for widescreen. With its constant chases and temple runs, a lot of the action in Indie’s movies is horizontal. However, for Jurassic Park, which featured a lot of large dinosaurs looming over helpless humans, Spielberg went with the narrower 1.85:1 aspect ratio. Well, I say, narrower, but in practice, it’s taller.

And here’s where we start getting into fights with filmmakers. Due to a lot of filmmakers - both amateur and professional - slapping black bars onto their footage by default, widescreen is often treated like cropping into an image rather than adding more space to the sides. In terms of composing an image, the latter is correct, but when it comes to displaying that image, the former is more accurate.

Most TVs these days are 16:9 or 1.78:1. It’s a wide rectangle, but not super wide like Cinemascope. This means that if you’re watching a widescreen movie on a modern TV, it will be cropped with black bars. Despite the wider image, the movie is taking up less space on the TV screen.

Now if you were to watch that same movie at the cinema, then the image would be truly wide and you’d instantly get a more epic viewing experience, right?

Not so fast!

Bigger is Taller

I used to think this was the case and it still is for a handful of venues, but most multiplex cinemas actually have 16:9 screens. So even on the big screen, a widescreen image is still smaller than 1.78:1. Only very old cinemas still do that fun thing of opening up the curtains at the sides of the screen before the movie starts. Most multiplexes just crop the image like it would be on a TV.

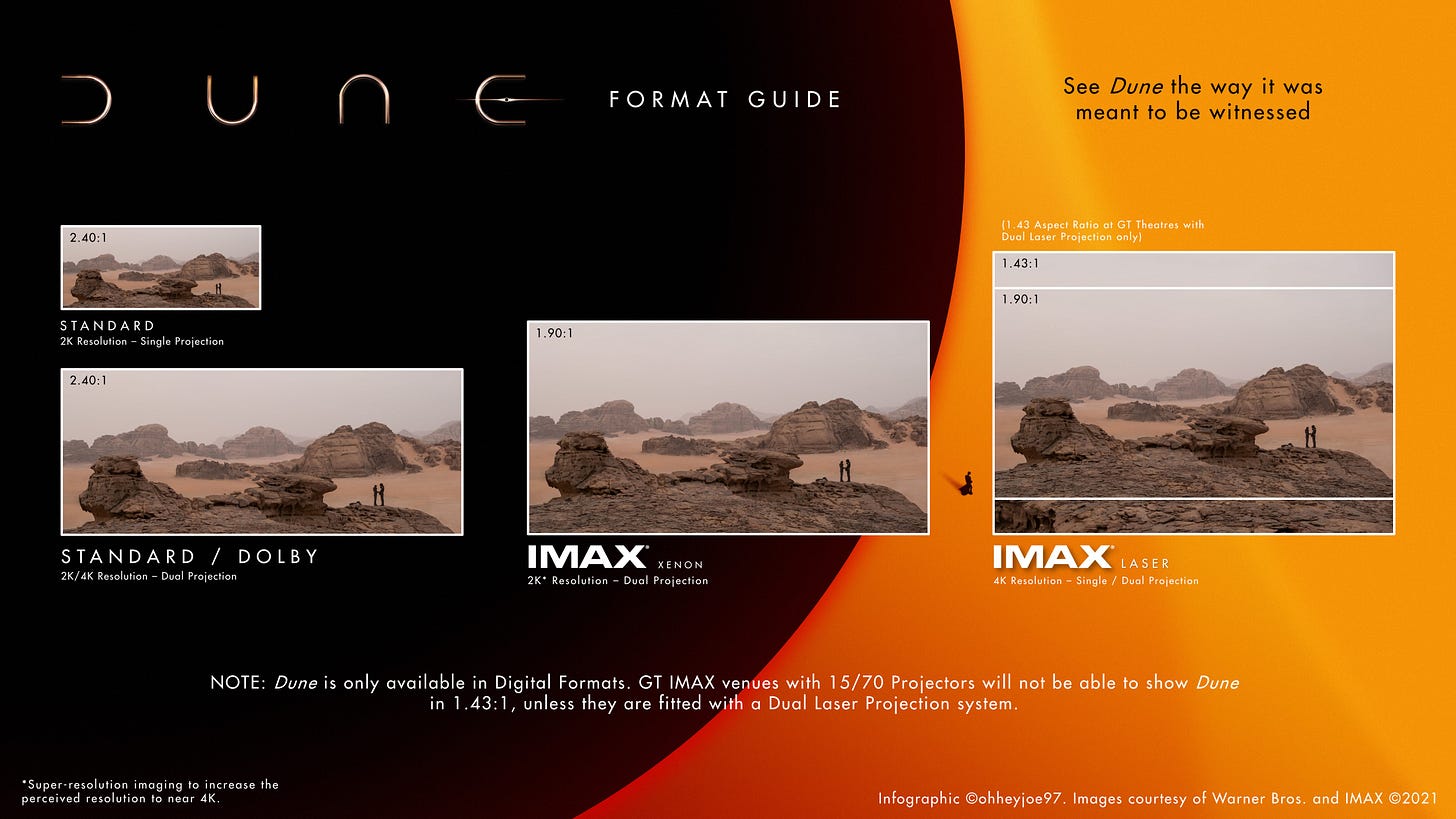

Even an IMAX screen is not wide, it’s tall with a 1.43:1 ratio, very close to our old friend Academy Ratio. This is front and centre of most IMAX movie marketing campaigns. Promotions for Dune and Avatar: The Way of Water made it a point to show people all the extra information they’d be missing if they watched the movies on a standard screen.

IMAX is essentially using the same marketing trick as Cinemascope in the 50s - sure you could watch Dune on your shitty TV, but you’d have a much better experience if you watched it on the much taller IMAX screen. Even Oppenheimer’s widescreen scenes used the 2.20:1 aspect ratio (the same ratio used for Lawrence of Arabia), which is quite wide, but not as wide as standard Scope.

The Limits of Widescreen

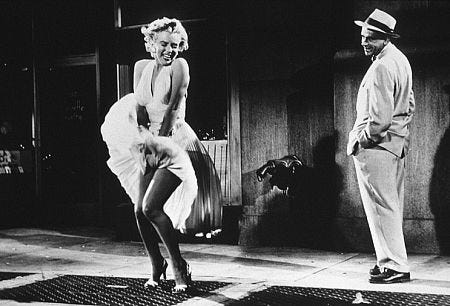

As a filmmaker myself, I honestly don’t like shooting in Scope. It’s far too limiting in terms of composition. Look at the above image from Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch. Notice how awkwardly placed actor Tom Ewell looks on the right. Because the director didn’t want to cut Marilyn Monroe’s head off when she climbed the stairs, Ewell is left as a floating head and shoulders.

But an even more damning example from this movie comes from its most famous image.

Everyone knows this iconic shot, but fun fact, it’s not even in the film. The actual scene creates this image in two shots. The Scope frame is too short to capture it. To get the full body image, the camera would have to be so far back that Monroe would have looked tiny. The above image is a behind-the-scenes photograph used mostly for marketing.

A 1.85:1 frame could have captured this no problem, but because Scope was in fashion, Wilder’s hands were tied. Thankfully this doesn’t seem to be a problem these days.

Is Widescreen Dying?

It would probably be more accurate to say widescreen is losing its monopoly on “cinematic” quality.

Despite its association with blockbuster movies, many of Spielberg’s biggest hits didn’t use it - E.T., Jurassic Park and War of the Worlds all used the 1.85:1 aspect ratio. James Cameron’s Avatar used 1.78:1 and its sequel used 1.85:1 (though for some reason the trailers are cropped to 2.39:1). Earlier examples include Pacific Rim and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes - both used 1.85:1 - and Zack Snyder even went for Academy Ratio for his cut of Justice League.

Modern blockbusters have more freedom than ever in creating their images and it’s great to see not only filmmakers embracing that freedom, but audiences appreciating it as well. After all many young people today are used to watching taller images on their various devices. I used to despise vertical video, but even I have to admit, some of the ways it’s been used are pretty cool.

A lot of ageing filmmakers and younger enthusiasts alike will drone on about “the death of cinema” which has apparently been just around the corner for several decades now. But changes like this make me optimistic. Perhaps we’re not seeing a degradation, merely a transformation.

What cinemas can offer is expanding, how audiences watch movies is transforming and what it means for a movie to look “cinematic” is no longer defined by the thickness of black bars.

I’ve thought that the inflection point was the introduction of HDTV, and its 16:9 aspect. That killed the “pan-and-scan” approach to transferring theatrical films to TV (eliminating that weird effect where the opening titles were squished) and I applauded it. Wider aspects were more easily adapted. I’ve never complained about top or bottom bars; modern, larger-screen TVs adequately compensate for the apparent reduction in image size.

Personally, I didn’t like the Snyder JL cut’s aspect. It was billed as Snyder’s “original vision”, but to me, it seemed more like a compromise among widescreen, HDTV, and the “academy ratio”. Make up your mind, Zach, and go with it, know what I mean? 🤔😉😊